Covid-19 voice complications

COVID-19 and Voice Problems

Giselle Maartens. Speech Therapist.

Our experience at the Pretoria Voice Clinic:

In South Africa, COVID-19 has been with us for more than a year now.

As an Ear, Nose and Throat Specialist (ENT) and a Speech Language Therapist (SLT) working in the field of voice at the Pretoria Voice Clinic, we are starting to see more and more voice, airway and breathing problems related due to COVID-19, in our clinical case load.

Literature has indicated that respiratory/pulmonary and laryngeal complications are associated with COVID-19 infection. This can influence people on a physical, functional, and emotional level. This poses a challenge for people who use their voices for their vocation, or for singers. Even in cases where voice is just used on a social level, if communication breakdown occurs due to poor voice it can have a negative influence on the message.

Respiratory consequences

Some of the most common respiratory changes following COVID-19 are fatigue and dyspnea/shortness of breath. Lung damage and respiratory sequelae can even occur in less seriously ill COVID-19 cases. While some pulmonary lesions will gradually heal and disappear, others can form scar tissue which stiffen the lungs, and cause shortness of breath. This could be debilitating for professional voice users, and even more so for singers and teachers of singing.

Laryngeal consequences

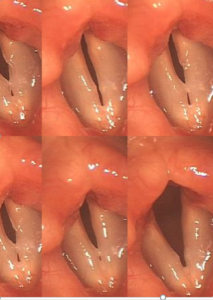

Any upper respiratory tract infection (URTI) causes inflammation of the upper airway, which includes the vocal folds. In the case of the COVID-19 virus, the virus itself causes inflammation. When an URTI affects the lungs, one can cough a lot. When you have COVID-19 you are likely to experience long periods of coughing that won’t stop. Coughing brings the vocal folds forcefully together to strongly force air out, clearing any mucous from the lungs and throat. The already inflamed throat and vocal folds from the infection experience quite a battering from this level of coughing which further irritates the vocal folds and laryngeal area. This increases the swelling of the vocal folds causing them to be stiffer and less flexible. This means they are unable to vibrate freely and the sound of your voice changes often to a raspy or rough quality, with a deeper-pitch and even reducing it to a whisper.

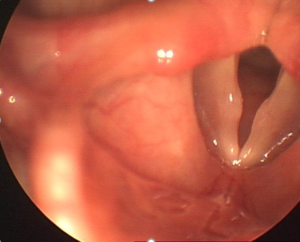

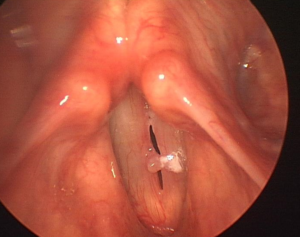

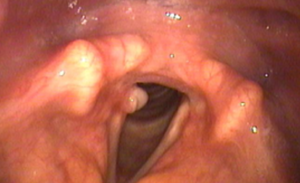

Prolonged intubation can cause potential damage to the vocal system and upper airway. Placement of the endotracheal tube irritate the throat tissue, making your throat sore and your voice sound raspy. Mild throat swelling or edema may occur after a breathing tube is removed. These symptoms of irritation and swelling can lead to coughing or frequent throat clearing which further irritate the vocal system. In cases where prolonged intubation was needed, glottis injuries are more common. Laryngeal abnormalities may include airway stenosis (narrowing), laryngeal stenosis below, at, or above the vocal folds, vocal fold mucosal / vibration abnormalities and scarring, vocal fold fixation (unilateral vocal fold immobility) and post-intubation phonatory insufficiency. These complications can cause hoarseness, difficulty swallowing and trouble breathing.

Other laryngeal complications involve vocal fold paralysis and paresis due to periods of intubation, or as a result from viral-related injury to the vagus nerve (responsible for vocal fold muscle function and sensation to part of the larynx). The possibility of developing laryngeal sensory neuropathy post COVID-19, may occur, as it can follow any viral infection.

In the literature it has been documented that singers experience respiratory compromise and complains of vocal fatigue post COVID-19 infection, indicating that singers may suffer lingering reduction of respiratory and phonatory function.

Other consequences

Chronic fatigue has been documented as a common consequence of COVID-19 infection, which can be associated with voice complaints.

Another affect that the COVID-19 pandemic has on voice and communication are on the educational community. Teachers and lectures are conducting classes online. This brings a whole new set of vocal demands to teachers and educators. Some of the symptoms recorded were dry throat, effort in addressing remote classes, hoarseness after giving classes, and difficulties with the use of headphones.

Diagnosis and treatment

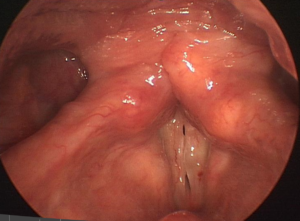

To diagnose vocal fold injury, scarring, paralysis or paresis, a view of the larynx is required to visualize abnormal tissue as well as observation of the function of the vocal folds. A video-stroboscopy assessment done by an ENT with a special interest in voice, can visualize the movement of the vocal folds and the mucosal wave.

Treatment for voice related complaints after COVID-19 infections include voice therapy. Voice therapy can sometimes help shrink scar tissue or abnormal growths on the vocal folds, and addresses functionality of the respiratory, laryngeal / vibratory and resonator systems. Some growths or scar tissue of the vocal folds or upper airway that can develop from breathing tubes require surgical intervention for removal.

What can you do to treat your COVID-19 hoarse voice?

Although you might not be able to prevent a hoarse COVID-19 voice, there are things you can do to treat it if you’re sick.

- Keep well hydrated.

Drink 1½ – 2 litres of fluid that doesn’t contain caffeine or alcohol per day (unless advised otherwise by a doctor).

Try gentle steaming with hot water. Breathe in and out gently through your nose or mouth. The steam should not be so hot that it brings on coughing.

- Try to avoid persistent, deliberate throat clearing, and if you can’t prevent it, make it as gentle as possible.

- Chewing gum or sucking sweets can help promote saliva flow, which lubricates the throat and can help reduce throat clearing. Avoid medicated lozenges and gargles, as these can contain ingredients that irritate the throat.

- A healthy diet, to minimize episodes of acid reflux that can exacerbate the situation in your throat.

- You do not need to be on total voice rest. Using your voice for a few short words every so often during the day keeps the vocal folds mobilised, and that is a good thing.

- Don’t deliberately choose to whisper, it puts the voice box under strain. Aim to use your normal voice, even if it sounds croaky. Avoid straining to force the voice to sound louder.

- Avoid talking over background noise such as music or television, as this cause you to raise your volume.

- You may notice that your voice becomes tired more quickly than normal. This is expected. Take a break from talking when your voice feels tired, to give it time to recover.

References:

- M R Naunheim et la. Laryngeal complications of COVID-19. Laryngoscope Investig Otolaryngology. 2020

- L Helding et al. COVID-19 After effects: Concerns for singers. Journal of Voice, 2020.

- K Nemr et al. COVID-19 and the teacher’s voice: self-perception and contributions of speech therapy to voice and communication during the pandemic. Clinics, 2021.

- J M Patterson, et al. COVID-19 and ENT SLT services, workforce, and research in the UK: A discussion paper. International Journal of Language Communication Disorders, 2020.

- Cleveland Voice Clinic post on website. What is “COVID-19 Voice” and what causes it? April 2021.

- Patient information. Therapy Department. “Advice for people experiencing voice problems after COVID-19”. NHS University Hospitals.

Covid-19 voice complications Read More »